Rather than congratulate the noble Baroness, Lady Kidron, if the House does not mind, I will quote her. At the beginning of her extraordinary film about children and the internet she says:

“About a year ago, I realised that every time I looked at a teenager, they had an electronic device in their hand, a device connected to the internet. I started asking questions. First the simple ones, like why can’t you leave that thing alone? And how can you do homework while checking Facebook at the same time? Quickly, I graduated to the more difficult: do you have any privacy settings? Do you know where your data goes? Do you know the person you’re talking to? Each of my questions was answered with a shrug. I always have and always will believe, that the internet could be the instrument by which we deliver the full promise of human creativity. But perhaps it’s time we asked ourselves: have we outsourced our children to the internet? And if yes, where are they, and who owns them?”.

I urge everyone interested in this debate to watch the noble Baroness’s extraordinary film, “InRealLife”. It teaches us so many things. It also reminds us that policymakers in general and politicians in particular need to recognise that we are at best digital tourists. However, that cannot prevent us legislating on behalf of digital natives—young people who live and breathe the internet. Indeed, it is our responsibility. That is where the problem, to which the noble Baroness, Lady Kidron, alluded at the beginning, lies, because we are trying to govern the terrain of digital natives. With a few honourable exceptions in this House—today they are the noble Baronesses, Lady Kidron, Lady Shields and Lady Lane-Fox—the rest of really do not have a clue what we are doing. Let us be honest, in comparison to the digital natives, most of us are digitally housebound agrophobes.

“Agoraphobe” is an interesting word in relation to how too many of us in politics instinctively view the internet. It comes from the Greek “agora” meaning market place;, which is similar to what a first-century Roman might call a forum or an open space, or what a 21st century teenager might call cyberspace. According to Wikipedia, agoraphobia is,

“an anxiety disorder where the sufferer perceives certain environments”—

let us think of the internet—

“as dangerous or uncomfortable, often due to the environment’s vast openness or crowdedness”.

In another online forum I found an agoraphobe described as,

“someone with a morbid and irrational fear of the outdoors, and in particular, of crowded public spaces.”

There we have it. That is basically us in the House of Lords when we view the internet. We view it in a morbid, irrational manner because we instinctively find it dangerous and uncomfortable. It is dangerous because none of the rules that we were brought up with apply; and uncomfortable because we cannot navigate the vast terrain. We do not know how to get around, and it seems hideously overcrowded because the whole wide world is there, otherwise known as www. For the younger generation, everyone is there, yet we, the digital tourists, can barely connect a computer to a printer or upload a blog.

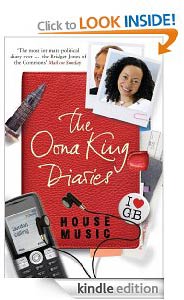

I am not even joking. This is a really bad thing to say and I apologise in advance. If your Lordships go to my website www.oonaking.com - that is unforgivable, I grant you, but let me explain—you will see that my penultimate blog entry is dated July 2014. The next one is from this month, November. There are four months in between. Contrary to public perceptions of politicians, that is not because I was on holiday for four months. It is not because I did not have anything to blog about for a third of a year. It is because, despite being shown on four separate occasions over a three-year period how to upload a blog to my website, I just cannot do it. I don’t get it—it does not stick in my brain, because I was not brought up on computers, or I have not spent enough time learning how to navigate them. Let me put my cards on the table: I hate computers; they never work for me. I know that if I try to upload a blog, it will take four hours out of my life, it will end in failure, I will lose the will to live and I may sob hysterically. So, like many noble Lords, I distrust computers and I cannot effectively navigate the vast terrain of the internet.

Of course, when you are in that position, you would rather think the internet is a place ram-packed with paedophiles and con-merchants, because then our agoraphobia would be a blessing not a curse. Now here is the thing again: the internet is ram-packed with paedophiles and con-merchants, because the internet is the real world through another lens. Think of the real world and go back a few decades to, say, the 1970s. It turns out there were paedophiles everywhere you looked, from “Jim’ll Fix It” to the political establishment to “Top of the Pops”.

Police forces across Britain are today investigating 7,500 child abuse cases, including historical cases at children’s care homes. We all know that humans can be monsters, whether online or offline, and humans can be angels, online or offline—creative, inspiring, empathetic and transcendent. Between those two extremes is everything else. The internet means that children can come into contact with greater numbers of monsters or angels than ever before. The monsters we know about are predatory online paedophiles. The angels are, for example, the online mentors who can literally transform a young person’s life for the good. The noble Earl, Lord Listowel, mentioned some of the mentoring that takes place.

The noble Baroness, Lady Shields, in her excellent maiden speech, spoke about the need for the creation of digital content to be safe by design. She said that we in authority must be faster, nimbler and more innovative than the minority of perpetrators who use the internet for criminal purposes. The We Protect initiative mentioned by the noble Baroness is also hugely important. She may also have suggested—I will be corrected if I am wrong about this—that we should close loopholes when people try to get around the structures we are building.

Action on what can be done falls into two distinct camps. On the one hand, we need to prevent the worst excesses and online abuse. In the context of today’s debate on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, we are talking about Article 16 on privacy and Articles 19, 35 and 36 on protection. The second part of what we need to do is to educate children and to be critical and self-aware users of the internet—not used and abused by the internet. That is covered by Article 17 on mass media and Article 31 on the right to recreation and cultural activities, and the right to self expression.

On preventing the worst excesses, we need to move beyond the question of whether we should regulate the new wild west of the internet to how to regulate it. Obviously, there has been a huge amount of discussion on this, but we realise that there are things that we can and must do to protect our children. On extending that protection, we heard powerfully from the noble Baroness, Lady Howe, to whom I pay great tribute for the work that she is doing. We have recently discussed her proposals on adult content filters in the Consumer Rights Bill, and I must say to the Minister that I am genuinely perplexed by the Government’s position. It makes no sense that the Government go out of their way to get protection from the four main ISPs but then leave a loophole in which 10% of houses and the children in them will have no protection from adult content filters. What will the Minister do to get his colleagues to change their view and position before we get to Third Reading? There are the other issues, such as making online billing an offence, as the noble Baroness, Lady Warwick, outlined, and revenge porn on which the noble Baroness, Lady Uddin, spoke powerfully.

On the second part, educating children to be critical and self-aware, we need to push digital literacy right up the political agenda. I think that the iRights agenda is a fantastic place to start, with its five key principles. First, all under-18s should have the right to delete data that they have posted. Secondly, we should have the right to know who holds our data and who profits from these data—we would all like to know that, would we not? Thirdly, under-18s should be able to explore the internet safely. Fourthly, there should be safeguards on compulsive technologies, such as gaming. Fifthly, users should be educated so that they can navigate the terrain. I would say that we need iRights for Members of the House of Lords as well.

The noble Baroness, Lady Lane-Fox, outlined the plight suffered by 10 million adults in the UK who are still barred from the benefits of the internet. I cannot speak highly enough of the work that she does to close the digital divide, which has never been more important.

In conclusion, we heard from the noble Baroness, Lady Kidron, that children’s lives have been revolutionised by technology, and that we must take this opportunity to ensure that we build a rights-based approach to children in the digital world. That is the lesson of this debate. It makes sense for a rights-based approach to stand on the architecture of the UNCRC. I thank the noble Baroness again for securing this debate and ask her forgiveness if I do not blog about it.