Although I am evangelical on the subject of adoption—even more evangelical than the Secretary of State in the other place as I have three adopted children—to focus on adoption at the expense of other permanent care solutions would inevitably be to neglect over half our children in care. That simply is not an option.

The best way to help children in care is to change circumstances in their birth families so that they are not taken into care in the first place. That is why every single member of the committee to speak so far has brought up the subject of early intervention and the fact that the grant was raided, manoeuvred or manipulated. Whatever word you want to use, the Government announced they were taking £150 million from councils’ early intervention grants. The Government argued they were doing so because adoption is a form of early intervention. Of course that is true but the whole point of “early” early intervention is to prevent children being removed from their birth families in the first place. In that respect, adoption is not early intervention but an act of last resort when all else has failed.

Worryingly, we heard time and again that either families today are failing more and more often or their failure has now become unacceptable. Whatever the reasons for that, the upshot is clear: we heard again and again that the water table is rising. All the professionals we took evidence from were alarmed by the rising tide of children coming into the care system. If more money is taken out of early intervention then even more children will be put up for adoption. The NSPCC has said:

“Whilst we welcome more support for adoption it simply doesn’t make sense to take the money from the early intervention pot. This funding actually helps stop family breakdown which often leads to the need for adoption in the first place”.

I understand that the Minister will state that early intervention funding is increasing in 2014-15, up from 2011-12, but I have been told by various local authorities that this does not make up for all the money that they have lost.

While we are on the subject of money, I want to mention post-adoption support. This was one of the committee’s most important recommendations. We proposed a statutory duty to co-operate so that families which adopt Britain’s most vulnerable children receive the professional help they need. Of course, they do not know when that help will be required. It might be six weeks after they adopt a child or it might be six or 10 years. We are talking about children who have been abandoned, neglected or abused—whether physically, emotionally or sexually. They may be withdrawn when they arrive at their new families. They may be physically aggressive towards their new parents. I have spoken to many adoptive parents who were literally taken aback at what hit them when newly adopted children arrived in their families. The idea that these new parents should be left to deal with the consequences of early abuse and neglect is unconscionable. It is also financially irresponsible. The costs of adoption breakdown are met by the state and it is invariably more expensive to take a child back into care than to give those families the help they need at the appropriate time.

The Government themselves state that there is a strong moral and financial imperative for providing high-quality adoption support. I welcome that statement, but if they are to stand by it, will they please undertake to review the committee’s suggestion of a statutory duty? If the Minister does not think that a statutory duty to co-operate among the different agencies that provide such services—such as the NHS, adolescent mental health services, or whatever—is appropriate, will he agree to review that advice on statutory support, as it is a lifeline to adoptive families?

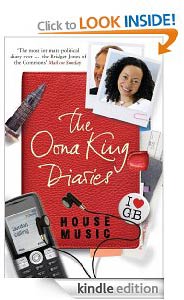

I also welcome the Government’s commitment to equalising rights between adoptive parents and non-adoptive parents. I was contacted by an adoptive parent who was forced to return to work early. She was not eligible for statutory maternity pay because her child was adopted and she worked freelance. If you are freelance and you have a baby, you receive SMP, but if you are freelance and you adopt a baby, you do not. I know that that is true because the same thing happened to me. I submit that I am more able to deal with that situation than many freelancers. It is iniquitous and a clear case of discrimination that if you adopt a baby and are freelance, you do not get the same support as if it was a birth baby. That is despite the fact that an adoptive child has an even greater need than a birth child to form healthy attachments with its new parents. I should be very grateful if the Minister would undertake to write to me on the issue, if he cannot give a response at this point.

Social impact bonds have been mentioned by other noble Lords. The Government say that they are monitoring innovative funding mechanisms such as social impact bonds. Do they have any plans to use social impact bonds to fund post-adoption support? What more can the Minister tell us about that?

I end by thanking the chair of our committee, the noble and learned Baroness, Lady Butler-Sloss, for her excellent leadership. I imagine that her breadth of experience on the subject is almost unparalleled in this House, notwithstanding the many experts we have here. I also thank those who so ably helped the committee in its work. It was an absolute pleasure to serve on the committee, but it will mean something only if the Government can take firm and clear steps in the areas that we have outlined so that our desire to give Britain’s most vulnerable children a fair chance in life becomes reality.