It takes several years and 400 pages for the pain to seep out, during which Obama tries to unlock “the puzzle of being a black man”. The puzzle is complicated by the fact that his family is white. Like so many mixed-race children, including myself, he is brought up by a white mother and white grandparents. He wants to believe that black and white can get along, because otherwise his existence must be at best a mistake, at worst a lie.

That existence takes him from his childhood home near the beaches of Hawaii, to the markets and slums of Jakarta, and then to Los Angeles., New York and Chicago. He went to local schools in Indonesia from the age of six until 10. His mother woke him at 4am each morning for English lessons so that he didn’t fall behind. “This is no picnic for me either, buster,” she’d reply when he complained bitterly about his early starts.

He writes about his mother with great affection and admiration, saying that: “What is best in me I owe to her.” And yet, as the book’s title suggests, mostly it is concerned not with his white mother but with his black father. The primal wound of parental abandonment, added to the search for identity within white mainstream society, means that his journey of self-discovery must uncover the black part of him, not the white part.

At university he feels unable to fit in with white students, yet constantly has to prove himself to black students. When a right-on black comrade claims that his choice of reading – Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad – is a racist tract, Obama replies: “I read it to help me understand just what it is that makes white people so afraid. Their demons. It helps me understand how people learn to hate.”

“And that’s important to you?” asks the friend.

“My life depends on it,” Obama writes.

There is an authenticity to the book that makes you think he might really be driven by the quest for common ground; the desire to diagnose the phenomenon of hate, and to come up with a prescription; the desire to prove that what unites us is greater than what divides us.

This desire to bring harmony is not purely a Ghandi-esque display of altruism, but also an act of survival. He finds some of the answer to what feeds hate in his grass-roots work. He tries to bring hope to desperate communities in sink estates around the decaying hulk of Chicago’s industrial past, and has a surprising level of success. You have to admire him for it, especially if you’ve ever tried to mobilise local communities mired in poverty and depression.

Obama explores the extent of African-American rage in the face of white incomprehension (why are black people always angry?). But, although the book deals with race and class, it’s real strength is in revealing the flawed human psychology, black and white, that can lead any person towards misunderstanding, prejudice, despair and poverty. Much of the book is also a meditation on loneliness.

Obama is constantly an outsider in search of real community, a community he finally finds in Chicago – which he goes on to represent in the state legislature, before being elected to the US Senate, where today he is the only African-American Senator.

Obama writes candidly about himself as well as about the race divisions that maim America. He delineates people with a rare skill, using individual shortcomings to describe the hurt and failure of a whole society. And he does it in a language most politicians cannot speak, talking of moon-washed streets, computers that flash emerald messages around the globe, and the dun-coloured plains of the African savannah that seem supple as a lion’s back.

Recognition of his own ultimately privileged position, and empathy for others, comes off each page. He stands as a 10-year-old at American immigration control, behind a Chinese family who had been lively and animated during the flight from Jakarta. But “now the family was standing absolutely still, trying to will themselves invisible, their eyes silently following the hands that riffled through their passports and luggage with a menacing calm. Finally the customs official tapped me on the shoulder and asked me if I was an American. I nodded and handed him my passport. ‘Go ahead,’ he said, and told the Chinese family to stand to one side.”

Obama’s background gives him a heightened ability to understand antagonistic world views. He believes in the power of words. “If I could just find the right words, things would change.” A decade later he proved this point at the 2004 Democratic Convention when he was chosen as the keynote speaker. The words he picked made him an overnight celebrity and political sensation.

What does this book say about Obama the politician? It is proof positive that he is a “listening” politician; he couldn’t otherwise have depicted the myriad lives that come off these pages. It also demonstrates his capacity to provide compelling narrative for the human condition.

The book’s epilogue ends with him at his own wedding in 1992, toasting “a happy ending”. Becoming America’s first black president would certainly be a good beginning.

Dreams from my Father by Barack Obama

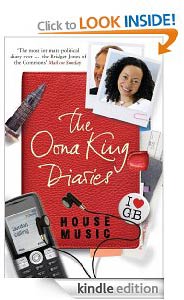

A review by Oona King, published in The Times 7 September 2007

Book review: Obama's Dreams from my Father

Book review: Obama's Dreams from my Father